Personal stories illustrate why we need a medical aid in dying law

Tell us your story

We are always looking for personal stories focused on end-of-life experiences and we would like to hear from you, your family or your friends. Stories from Arizonans are important because they demonstrate to lawmakers and others the importance their constituents place on end-of-life choices. If you are uneasy about your writing ability, not to worry—we will help you get your story told.

Many of these stories have been included in the booklet Arizona Voices for a Medical Aid in Dying Law.

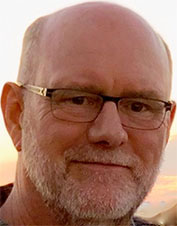

“I’m an oncologist with terminal cancer, and I support medical aid in dying. Here’s why.”

Dr. Tom R. Fitch volunteers as Medical Director for Arizona End-of-Life Options, where he shares his extensive medical experience and professional wisdom with our organization. His distinguished career as an oncologist, hematologist and palliative care physician spans 30 years of service to his patients. He most recently retired from the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale after 17 years with that premier organization. Today, he faces a wholly different medical challenge. This article appeared in the Arizona Republic, May 30, 2020.

Remarkable advances in medical care are helping us live longer. But that means there also are an increasing number of people living with advancing serious illness.

The vast majority understand they are living with a terminal condition, yet they and their families are unprepared for the final stages of life. Relatively few have had discussions with their physicians about their prognosis and end-of-life care options. Their wishes and goals are not discussed, and no meaningful informed consent regarding further disease-directed treatments is provided.

“Let’s try this,” becomes the default recommendation, and patients are commonly led down a path of relentless disease-directed therapies of limited to no benefit. Tragically, more treatment too often results in more suffering and shortened survival.

With the expert end-of-life care currently available, dying and death can be meaningful and peaceful for many. But to believe all deaths are “natural” – peaceful and without suffering – is just wrong.

I cared for patients with cancer for more than 30 years and increasingly provided palliative and hospice care over the final 17 years of my career. I saw agonizing deaths despite my best efforts, and it was not rare for patients to ask me how I might help accelerate their dying. That, however, was not an option in either Minnesota or Arizona where I practiced.

Patients must understand their options

Now, I too am faced with terminal illness. I have multiple myeloma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and despite aggressive care, I have not achieved remission. My cancers are incurable.

I contemplate dying and my death and those thoughts include consideration of medical aid in dying. I do not know if I would ever self-administer a lethal dose of medications, but I pray that the option is available for me.

I do know that we must help patients and families overcome the taboo of discussing their prognosis, dying and death. We need to facilitate meaningful end-of-life care conversations among patients, their families and health-care providers; promote the completion of advance directives; and encourage discussions of patients’ wishes, goals and values.

Patients and families must be informed of the many end-of-life care options available – including the expertise of palliative care and hospice providers, discussions regarding the possibility of stopping disease-directed therapies, withholding or withdrawing more advanced supportive care and/or devices, voluntarily stopping eating and drinking, and palliative sedation.

Patients near the end of their life also should have access to medical aid in dying (MAID).

What medical aid in dying laws do

I fully respect the conscience of those who oppose MAID; they are opposed for passionately held personal beliefs and values. I simply ask that they similarly respect my strongly held beliefs and values.

Guidance in the American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics understands this divide: “it encompasses the irreducible moral tension at stake for physicians with respect to participating in assisted suicide. Supporters and opponents share a fundamental commitment to values of care, compassion, respect, and dignity; they diverge in drawing different moral conclusions from those underlying values in equally good faith.”

MAID is now legal in nine states and the District of Columbia, available to more than 70 million residents. After nearly 50 years of real-world experience, there has been no evidence of the “slippery slope” or “increased societal risk” opponents routinely cite.

We have seen no indication of a heightened risk for women, the elderly, poorly educated, the disabled, minorities, minors or those with mental illness. There has been no rising incidence of casual deaths and no evidence to suggest that MAID has harmed the integrity of medicine or end-of-life care.

MAID laws clearly provide adequate safeguards and allow for the position of dissenting physicians. The laws respect their conscience and give the right to any physician not to participate.

This is patient-centered care

Those of us who support MAID are asking for the same – respect for our conscience and considered judgment. We do not believe we are doing harm. We are caring for a competent adult who has a terminal illness with a prognosis of six months or less. We are providing patient-centered care consistent with the patient’s wishes, goals, beliefs and values – helping that patient avoid protracted, refractory and avoidable suffering.

One false narrative espoused by opponents – that “participation in MAID is suicide” – needs to be addressed. Participants do not want to die. They have a progressive terminal illness, and meaningful, prolonged survival is no longer an option.

They have full mental capacity with an understanding of their disease, its expected course and their prognosis. They have the support of their family. They feel their personhood is being destroyed by their illness, and they want their death to be meaningful and peaceful.

None of this is true for people who die by suicide.

Personally, I no longer struggle with the ethics, morality and other controversies surrounding MAID. Ethical principles and moral laws alone are just not sufficient to answer the complex questions surrounding an individual’s dying and death.

Our diverse country and our Constitution forbid us from imposing our own religious and faith beliefs on others. When we try, we are forcing others to conform to our beliefs and we are turning a blind eye from truly seeing the very real human suffering that is in front of us.

It is devastating for patients if we ignore their life stories, their family, their culture, and the impact of their disease and treatment on their life and well-being. The value of their life, as they define it, has vanished and they want to die on their own terms.

This is not a challenge to God’s divine sovereignty but a challenge to the disease itself. Patients are vowing that it will no longer be in charge.

As my cancers progress, I too want to be in charge. I want the legal option to die, if need be, before it is too late to consent to my own death. I desperately want to avoid recruitment into that borderland where I would vegetate as neither here nor there.

I ask for your unconditional trust and I ask that those opposed to MAID for themselves, respect my prayerful discernment and personal requests for end-of-life care as I believe it is consistent with my needs, beliefs and values.

Dr. Tom R. Fitch is an oncologist who has cared for cancer patients for more than 30 years.

I live in Arizona where medical aid in dying is not available. Fortunately, my sister didn’t.

By Spencer McCleave, MD

My sister Janet, ten years older than I, had had various health problems over the years, and had been on disability for a long time. She had developed renal failure on top of everything, and was on dialysis three times a week. After a year of that, she had had it. Getting back and forth to her dialysis appointments was challenging, but what really bothered her is that after each hours-long session, she felt exhausted. It took a day to recover, and then she had to go in and do it again. She was completely miserable.

She had four choices.

- She could continue with dialysis. At her age and in her poor overall health, she was not ever going to get a kidney transplant, so this would have to continue indefinitely, perhaps until some other health problem did her in. This option made her feel hopeless.

- She could stop dialysis. She would then fill up with fluid, feel more and more bloated every day, and have new symptoms that often go along with untreated renal failure. It might take her weeks to die. This was unacceptable.

- She could commit suicide. Tearfully she spoke about this to me, explaining that one day, while alone, she could simply disconnect her dialysis port, and bleed to death. Someone would find her, probably the nice woman who came by to help with her housekeeping. This seemed too ugly to consider.

- Her fourth option was medical aid in dying (MAID), something that is not yet available in Arizona where I live. On a phone call she told me that she had looked into MAID and had started the application process.

She completed the two interviews the MAID program required, which showed that she understood the process and was able to consent. As she put it, they could see that she wasn’t “crazy” and knew exactly what she wanted.

I flew to be with her, arriving a couple of weeks before the selected date. She was intensely focused on getting her affairs in order, such tweaking her Will and making sure who was to get which knickknack.

At first she referred to her upcoming “procedure.” We gradually all learned to use the term MAID, and speak more directly about what was going to happen. No one in our family had any direct experience with MAID, so we floundered and struggled with our emotions and how to talk about it. Some moments were touching, others surreal. No one questioned her right to take control and make the decision she did.

Her wonderful doctor explained everything calmly and clearly, even getting a chuckle out of us by commenting that Janet certainly knew what she wanted and had been determined to see it through. He “got” her and we recognized that.

About eight of us gathered to support her but she decided who would be with her at the last moment – just me. I sat on the bed by her feet. The whole thing took just a few minutes, and was as calm and peaceful as could be. She simply faded off.

As I left the room, I told my brother that this was the hardest thing I had ever done in my life. But for her, it was the only sensible choice. I’m grateful it was available to her.

Why I am so Passionate about Medical Aid in Dying

by Janice Campos, RN

Volunteer, Arizona End-of-Life Options

It was September of 2014 when my husband collapsed in our bedroom. Blood and stool gushed onto the floor beside the bed, and he told me he was dying. I called our cardiologist who promptly ordered hospice care to begin the following day.

As an experienced RN, I felt competent to care for my husband and had retired the year before in preparation for this day. The signs of his decline had been increasing. His cardiac issues had begun 25 years earlier when he had collapsed at work and found to be in a third-degree heart block. A pacemaker had been inserted and since then, he underwent three pacemaker insertions, a quadruple bypass surgery, two knee replacements, and the successful removal of his sigmoid colon due to stage 2 colon cancer. When he became lost in our kitchen after one of these surgeries, his cardiologist diagnosed him with mild cognitive impairment explaining that the filtration of those early heart-lung machines sometimes allowed small clots to get into the circulation, causing damage to the brain.

It was during the last six months of his fourteen months of hospice care that he gradually began to eat and drink smaller amounts and solid foods became a thing of the past. At this point, his primary care physician advised that I stop giving him his meds for arthritis. I knew that this would eventually cause him much pain. I administered the Ativan, morphine, and atropine as the hospice nurse instructed, but they seemed to have less of an effect as time went by and I began to feel more and more helpless and much less effective as a caregiver. His strength dwindled and he became less able to help me pull him up in bed. One day he asked me to give him the whole bottle of Ativan and I informed him painfully that I still had a nursing license, so I could not help him.

On another day he asked me to find another gun because he could not pull the trigger on his loaded .38 caliber pistol. As an orthopedic physician who had also practiced psychiatry, my husband knew better than most that he would just deteriorate to the point of total helplessness, unable to do anything for himself. While I was glad he could not choose this option, it left both of us knowing that there was really no other recourse than to allow the natural course of events to unfold, however painful they were.

During the last four weeks of his life, his pain became worse, to the point that he could not stand to be touched. His skin broke down, no matter what nursing care measures I took to help it heal. The flotation mattress had no real effect and he suffered in horrible pain and agony. I felt helpless, and I knew I had reached the point of serious exhaustion, both physically and mentally. Two of his four adult children came for only short visits. I felt alone and utterly abandoned except for the caring of the hospice staff and my personal friends.

My wonderful companion whom I had worked and traveled with for 40 years lapsed into a coma and died without having his dignity and self-respect intact. I sincerely hope that my experience will help others realize that we need a way to legally allow those who are not going to survive, the right to die in a way that eases their misery.

Bill Rodgers: “No matter what hospice did, Joanne’s suffering was relentless”

Eight days before my wife passed on, she told me she wanted the struggle to end. She really wanted to use medical aid in dying, which in Arizona was absolutely not possible. We don’t have it. I had expected hospice to keep her comfortable through the final days, but I watched helplessly as my wife moaned loudly and lay unmoving with her head rolled to the side. One day I called hospice nurses to our home four times to try to find a way to alleviate her suffering, but they couldn’t make Joanne anywhere near comfortable.

It was such an undignified, inhumane ending for a beautiful lady who was never seen not looking perfect. After three especially terrible days she passed away on February 6, 2023. Those last days of suffering destroyed me; I turned toward Joanne’s bed and promised I would do everything I could to work toward getting medical aid in dying in Arizona.

Joanne was a dignified and private person who prided herself in always looking her best. Even until her last few weeks, at her behest I would lift her out of bed and into her wheelchair, and roll her into the bathroom to do her hair and makeup. We’d then spend the rest of the day on the sofa, just she and I at home. It was never out of vanity; that’s just the way she wanted to live.

Joanne and I met on Labor Day 1969 and were married in December that year. We decided very quickly that it was meant to be, and it lasted 53 years.

During the end of 2021, Joanne started experiencing extreme fatigue and weakness, which led to ultimately finding out that it was cancer in July 2022. She had a large malignant growth in her colon, and the cancer had already spread to her lymph nodes. The oncologist suggested surgery but warned that at 78 and being seriously anemic there was a chance Joanne would not recover. A second opinion from Mayo Clinic proposed a treatment plan of back-to-back surgery and chemo, but also stated that recovery was questionable. The cancer was so advanced that treatment would likely have ended any quality of life Joanne had.

Joanne worried that if she pursued treatment she would never have another good day in her life. She felt mostly good at the time, and in lieu of treatment she decided to live out the remainder of her life as best she could.

Home hospice met with us. I was filled with hope, thinking that hospice would be able to keep Joanne sufficiently comfortable and help her pass peacefully. We didn’t have medical aid in dying in Arizona, but now with hospice involved, I thought things were going to be OK.

Joanne was strong and determined, and chose to live as good a life as possible as long as possible. In December, when her legs could not support her to stand or walk, she used a wheelchair to continue going. She became confined to her bed in mid-January, and on January 29 she shared that she had endured all the suffering that she could withstand.

The following days were a rapid decline. She was in constant agony, struggling for every breath, moaning loudly. It went for hours. Hospice nurses said this is common and she does not know she is doing it, yet they also said she has her sense of hearing to the end and hears everything we say. No matter what hospice did, Joanne’s suffering was relentless. I was beside myself. Her final three days, she was mostly unconscious — but as our son and I were by her bed Sunday morning, she pleaded, “Help me, please help me.” It was devastating. That told me that she was in there, aware of her pain, waiting desperately for the end.

Joanne should not have been required to endure those last eight days. She did what she could to continue living, and she didn’t want to give up early. But she had gone as far as she could.

When death is approaching, each person deserves the right to meet it on their own terms. If we had medical aid in dying available, we would have requested the prescription by December when it became clear her decline was speeding up. We could have had a quiet, peaceful kiss and hug goodbye, and her life could have ended gently.

My beautiful wife passed away the next day. My grief has been tempered by the fact that I didn’t want her to suffer one more minute. It was just so terrible. It was such a relief when she took her last breath and had everlasting peace. Finally, her suffering had ended.

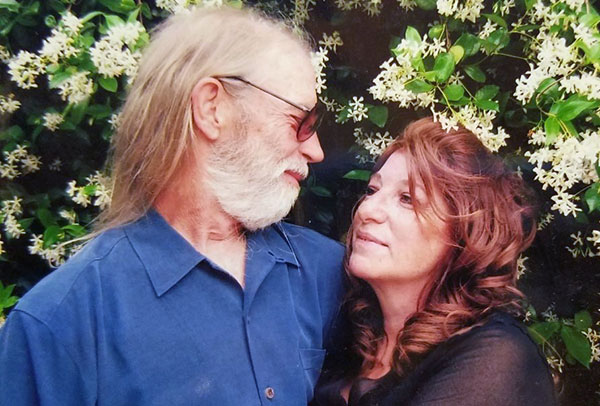

Lynn Lane: No one should have to experience the pain and the death that my husband endured

Lynn and Richard in 2015

Lynn and Richard in 2015

You never think it will happen to you. In August 2020, after my husband Richard contracted COVID, we said to each other “Well, at least we dodged the Big C.” If we only knew then….

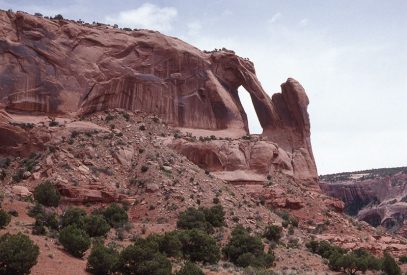

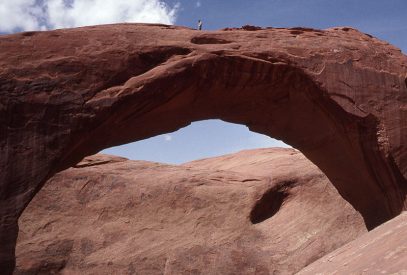

Afterwards he just couldn’t seem to regain his strength, but in March 2021 we took a summer job in a campground in Utah. On the way he complained of pain in his right groin area. The pain continued and he finally went to see a doctor who put him through a battery of tests. Then he got the dreaded news — cancer in several places and a recommendation that we immediately return to Arizona for treatment. Back in Arizona we met with an oncologist on April 4. More tests and more x-rays and more scans and biopsies — just continuous or so it seemed.

The oncologist confirmed urothelial bladder cancer with metastasis to the bone. Prognosis: 2 years with treatment; 4 months without treatment. He began a regime of chemotherapy which did not sit well with him. His bones were so affected that in May he broke his upper left arm just by rolling over in bed. May and June consisted of 911 calls and ambulance rides and we spent much time in and out of emergency and hospital rooms. He tried to continue with chemotherapy but grew weaker and weaker. Finally he was scheduled for an infusion in late June 2021 but had a high temperature so they admitted him to the hospital. Platelet counts, WBC and RBC were off the charts. He decided (and his oncologist concurred) that he could no longer endure the chemotherapy and he came home on June 27 under hospice care.

We set up a hospital bed in our TV room and that is where he remained until he passed on August 8, 2021 — a mere 136 days from diagnosis. This had been an above average healthy man. We enjoyed a very active life up until late 2020. Richard was a loving husband, father and grandfather.

My family and I had no choice but to watch his slow demise. He prayed for God to take him so many times — he had significant pain — and I prayed for this outcome as well. He went from 175 pounds to less than 130 pounds. He would certainly have used the medical aid in dying option had it been available to him to ease his suffering.

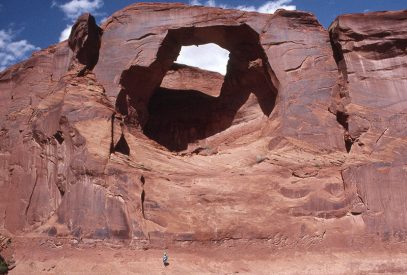

Richard on June 30, 2021

Richard on June 30, 2021

The family gathered on August 7 and stood vigil at his bedside, counting the seconds between breaths as we held our own at the same time. We all watched as his breaths became further and further apart until there were no more. At this time I promised myself that I would fight to ensure no one else would have to experience the pain and the death that he endured. At 1:22 am on August 8 he left this plane.

My husband’s story is being told to help others understand the heartbreak that no one should have to undergo. No one should have to live needlessly in pain and die in pain because of other’s beliefs. My husband’s final weeks/days felt like a disgrace to his beliefs. Others need to understand what it is like to watch a loved one suffer at the end of life, their loss of dignity, loss of autonomy, loss of quality of life, and why it is so important to give them the choice and control over how they want to die.

Medical aid in dying is not assisted suicide. It is the complete opposite. People who commit suicide want to die. People who have been given a prognosis of less than six months to live want nothing more than to keep living … until they decide they have had enough with the unrelenting pain and treatments and need to leave this Earth.

I now live with my steady companion — grief — night and day. It comes at the most awkward moments. Sometimes just a wave of emotion. Other times a tsunami that swallows me up and takes my breath. It is an unwanted companion and a relentless reminder of what we could have had.

Craig Moore, father of AZELO leader Dwight Moore, did not have access to a medical aid in dying law.

Craig is pictured dancing with granddaughter, Sasha, at a family wedding celebration.

Craig is pictured dancing with granddaughter, Sasha, at a family wedding celebration.

By Dwight Moore

My dad (Craig Moore) lived 93 vibrant years. He was curious, social, adventurous, and in love with my mother for 64 years until her death. He lived a long and full life. But, in his 94th year he developed “failure to thrive,” a multifactorial state of decline where most of his systems began to shut down.

He moved from his independent living apartment in Bethlehem, PA, to an assisted living unit in the same facility. That is when he called me at my home and asked me to “come out here and be my coach.” I knew immediately what he was asking. He was a lifetime advocate of death with dignity and leaving this world on his own terms. Unfortunately, Pennsylvania did not have a medical aid in dying law (and still doesn’t) so he made the decision to stop eating and drinking and recognized that he would need support.

Years earlier, Dad had written out his wishes. He said we would know that he was “done” if he became “confined”… no longer able to move on his own, no longer interested in reading three newspapers a day, no longer attracted by food, and not interested in his customary gin Martini.

After I arrived at his care facility, we talked at length about his readiness to die. My sister, Sara, arrived soon after. It was obvious to both of us that Dad, indeed, had reached the point he had written about years ago. He was crystal clear in his refusal to endure further medical treatment and gently explained that he was “done.” He qualified for hospice care, and they helped manage his bed sores, his daily bath, and attempts to eat. He had already decided that he needed to begin the process of voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED).

He notified his doctor, his family, the nursing staff, and the administrator of the facility about his intentions and told them that his “coach” would be helping him. In reality, I ended up being more of a linebacker than a coach, as I had to fend off well-meaning staff who wanted to give him ice cream, insert a PICC line for long-term administration of antibiotics, minimize the amount of morphine he was getting, and, in general, talk him out of his decision. At each staff shift change, Sara and I had to re-explain his wishes. The whole medical establishment pushed for him to stay alive despite his steadfast directive that he was ready to die.

It was difficult to witness. His pain and anxiety caused him to twist in his bed sheets, mutter about a secretary who couldn’t take dictation, writhe in discomfort in his bed, and occasionally yelp. To help quiet him, I asked his hospice team to increase his morphine dosage. Only then did he become more peaceful.

Near the beginning of his ordeal, he told me that the first two days were “hell.” Mercifully, he only lasted five days from when he stopped eating and drinking. Sara and I took individual “shifts” staying with him and leaving to catch some uneasy sleep in between. For reasons I don’t recall, we were both with him, holding both his hands, at 3:00 a.m. when he calmly drew his last breath. Unsettled and worn-out, Sara left shortly afterward. I stayed long enough to watch the funeral home attendants put him into a body bag and take him away. At that point I lost all composure.

It was my father’s desire to die with dignity—to conclude a life of self-reliance with a death that would allow him to exit gracefully before the pain and helplessness became unbearable. In part, that is why I have been an advocate and activist wherever I can help advance the cause of death with dignity in states like Arizona where such laws have yet to be passed.

Carla Wykoff: “It troubles me that I will likely not live long enough to have this option in my home state of Arizona.”

Carla Wykoff was a volunteer with Arizona End-of-Life Options until her passing. She agreed before her death to share details about her personal struggle with cancer and her concern about the Arizona legislature’s continuing unwillingness to pass a law providing residents access to medical aid in dying (MAID).

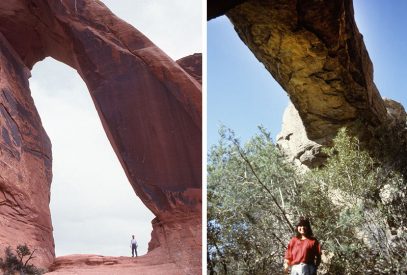

I am a long-time resident of Arizona, a retired engineer, scientist, teacher, and advocate for the desert biological diversity. I have been fighting lung and liver cancer for six years. I have endured surgeries, radiation, and the side effects of treatment.

I do not know how much longer I have to live. I am fighting the best I can but I am tired of being sick and I am exhausted by medical interventions. I do not want to die nor do I want to live in a weakened state, unable to do the things that have always given my life meaning. I want to live as long as I am able to get out into the wild places that are my source of spiritual energy.

But when my body signals me that my time is close, I want the option of ending my own life with dignity, enjoying the company of those I love—when, where and how I choose.

It troubles me that I will likely not have this option in my home state of Arizona—that others, whose beliefs I do not share, can and will force me to suffer pain and indignation in my last moments on the planet. I find that wrong, even barbaric.

I would like to thank my family and friends, and my doctors and other caregivers for their long support. I would like to ask you, my fellow Arizonans, to implement the option of medical aid in dying for all terminally-ill Arizonans who would prefer, like me, to end their lives on their own terms.

Video: Julie Jones, Prescott, Arizona

Below is a 3-minute video from Julie Jones of Prescott, Arizona, made in 2018. Terminally ill after 14 years of battling cancer, she discusses the choice of medical aid in dying.In Memory of Edwin J. McIntosh:

Another casualty of lawmakers’ failure to act

Edwin with his wirehair fox terrier, Christie.

By Marsha McIntosh, Sun City, Arizona

The morning my father fatally shot himself started out like most other mornings. My parents had coffee together, and my mother prepared to go to her exercise class. My father seemed especially anxious for her to leave the house.

When my mother came home, she was stunned to find my father on the patio floor with blood everywhere.

When the police arrived, they scrutinized the scene and routinely questioned my mother to eliminate her as a murder suspect. After all, there had been no witnesses to the shooting.

My father was an independent and vigorous man, having been raised on a Utah ranch. He worked hard all his life and took good care of his wife and four children. After his retirement, however, his health began to fail. He suffered from Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease for 10 years, and even the prednisone he took every day to help him breathe couldn’t help him lead a normal life or pursue his hobbies. Toward the end, he developed congestive heart failure and macular degeneration. He felt worse each day. He knew his systems were shutting down, and he needed assistance to perform the most routine daily tasks. He hated the thought of losing his self-reliance and could foresee a future of total reliance on my mother. The idea of needing so much help and feeling so poorly was simply not his idea of living.

My younger brother and his family, who my father loved to see, were coming to visit the next week. But my father felt time was quickly running out with his failing health and he saw no other options for his future.

After my father died, I began donating to Compassion & Choices, but I wasn’t ready to become active. I am now ready and am working with Arizona End-of-Life Options to make medical aid-in-dying a law in Arizona.

I often dream of how different it could have been if my father had had the option to use medical aid-in-dying to end his suffering. My sister and brothers could have been here to say goodbye. Most important, my father’s death would have been a much less traumatic situation for our mother.

Robin Toole: Having Control at Life’s End

Robin Toole of Tucson, a retired clinical social worker, has generously shared this story of her husband Don’s passing. A staunch advocate for Medical Aid in Dying (MAID), Robin has experienced the heartbreak of having a loved one take his own life in the face of unbearable pain and suffering.

Being born as the eldest child in a midwestern dairy farm family afforded Don an opportunity to practice a multitude of balanced values. He learned early on the difficult lessons of self-sacrifice, hard work and, most of all, compassion towards all living beings. He translated these values into a life of non-judgmental kindness and caring. He had developed a strong conviction that no life should ever have to end in suffering. This was his life’s mission.

His sparkling eyes and warm smile were noticed by all, along with his strong desire to help others. He had many passions and talents that he shared generously with people in his life. He was a musician and an athlete.

He cherished life despite having to overcome many challenges. He was a Vietnam Veteran. In 2002, he lost his first wife to a senseless school shooting at the University of Arizona. Nevertheless, he refused to allow these negative experiences to define him. He persisted with his kindness mission. His spirit was and remained unbroken.

Then, without warning, this energetic, vibrant man was stricken by mysterious symptoms—severe, persistent pain radiating from his inner ear to his jaw and head and difficulty swallowing. He fought hard to find answers. His doctors were stumped and while they searched for answers for two-and-a-half years, the pain and suffering were taking their toll on Don.

By the end, he was suffering unrelenting pain, had difficulty eating and speaking, experienced partial deafness and became progressively weaker. His suffering grew, and he was no longer able to enjoy the quality of life he so enjoyed.

Finally, one week before his death, he was diagnosed with a rare form of throat cancer which was attacking his nerves. He hemorrhaged from the biopsy site and was intubated to prevent choking. His vital signs were too weak to allow adequate sedation. He laid in the intensive care unit, helplessly frightened by this bodily invasion. He wrote me a note confessing that he had never experienced such terror. The intubation was removed after 24 hours and he went home with a gastric tube inserted for feeding.

His body was racked with pain and swelling, he had difficulty breathing and he felt constant fear. He spit up foamy, bitter fluid for 24 hours. The hope that he had held onto for years was now dashed by this new reality and loss of autonomy.

Having no ability in Arizona to receive medical assistance in death, Don took it upon himself to end his own suffering with a single gunshot. His death shouldn’t have had to be a violent one. This man who gave so much to others should have had a compassionate option at the end of his life.

I am blessed to have been married to this wonderful man. His life’s mission and values were an example to me and many others.

I emphatically believe that anyone who is terminally ill and facing similar circumstances should be given the option to have control at life’s end. That is why I urge Arizona lawmakers to pass legislation granting medical aid in dying in Arizona.

Barbara Paymaster: My Friend’s Peaceful Death — in Oregon!

Barbara Paymaster is a retiree in Mesa, Arizona.

August, 2018

One of my oldest and dearest friends used the Oregon Death with Dignity Act in April 2018 to end her life with peace and without pain. I share my friend’s story in the hopes that it will help strengthen the movement to provide death with dignity to people in my home state of Arizona and across the USA.

Ginny and I became friends when we were 3 years old. We met when we went to a dance class and our mothers became friends. In grade school, we grew even closer. We used to play at each other’s’ houses all the time. We even took a solemn vow to become blood sisters, cutting our index fingers and mixing our blood together to symbolize a lasting bond as only 10-year-old girls could.

Ginny and Barb, 5th Grade, 1959

Ginny and Barb, 5th Grade, 1959

We went our separate ways in high school and were out of touch for several decades. When we reconnected in 1990, it was for life. I visited her in Chicago, where we grew up, and later when she relocated to Arizona I helped her move into her apartment. Ginny relocated twice more, once to the East Coast and finally to Oregon. We always remained good friends through email and phone calls, always ending our conversations with “miss you” and “I love you.”

Well before she received a terminal diagnosis, Ginny had had ups and downs with various illnesses throughout her life. She had respiratory issues for many years and battled tuberculosis for a time. But it wasn’t until she was living in Oregon that a doctor discovered she had kidney failure, anemia, and vasculitis: a combination of ailment that would kill her within six months.

When she called me in January 2018 to relay the bad news, she couldn’t go out and do normal things because she was in so much pain. She did grueling medical treatments, but they just weakened her. She told me she was thinking about using the Oregon Death with Dignity Act to end her suffering.

I understood why she wanted to use the law. If that’s what you want to do, I told her, I will come out and be with you and support you through all this. Initially she said yes, but later decided that she only wanted her son with her when she ingested the medication. I respected her decision.

Ginny prepared well for her death. She cleaned out her filing cabinets; she canceled her credit cards; she put her affairs in order. She promised to send me a string of pearls I could use to communicate with her after she died. She’d always been very interested in the supernatural and wanted me to connect with her in the afterlife.

“Dearest Barb, my oldest friend, please know how much I love you and miss you and appreciate you,” she told me. “I will be around, look for me beside you, I will be there. I love you dearly.”

I promised Ginny that I would try to connect with her through her pearls, the way she told me to hold them, but if all else fails, every year I would reach out to her on the anniversary of her death and try to connect with her.

Originally, she had planned to ingest the medication on her birthday, March 30. Due to unforeseen circumstances, she had to push back to April 1. She decided she would take the medication at 11:00 a.m.: the 11th hour.

We spoke on March 30, Ginny’s birthday. I was glad to know that she had received my special birthday card.

“I know you wish me the best,” she said. She told me she was looking forward to her next life as if she were going on a trip. A few minutes into the conversation, I heard static on the line. A moment later, we were disconnected.

I texted her at 7:30 a.m. on April 1. My text read, “As the 11th hour draws near, I want to tell you that I love you. Until we meet again on the other side.” Not 10 minutes later, she called me.

“I can’t talk long,” she said, “but I wanted to tell you I love you one more time.”

I knew she had chosen some Eric Clapton songs to play after she took the medication. At 11:00 a.m., I put on Eric Clapton too. It made me feel like I was there with her.

At 2:00 p.m., I went into my kitchen. While I was standing at my kitchen sink, a plant on the counter caught my eye. Earlier in the morning, it was full-leafed and healthy; now, all the leaves had fallen off. Was Ginny telling me that she was gone? Was this a sign for me?

After she died, I went out of town for a time. When I returned home, I found a package waiting for me. Inside it was the string of pearls Ginny had promised. I was so excited.

I had a way to stay connected to my dear friend.

One day not long ago, I started thinking about how profoundly Ginny’s experience with the Oregon Death with Dignity Act had impacted me. I do not live in a state with an assisted-dying law, but perhaps I could help change that and honor my friend at the same time by sharing her story and showing people an example of what a good death could look like.

To Ginny, and to me, Death with Dignity means that you can choose the way that you would like to leave your present existence. This is not suicide. This means you are at the end, choosing to go before it naturally happens.

Ginny taught me how to say goodbye to people, how to plan so that you don’t have to be a burden to anybody else, and how to leave the world with grace. The freedom and autonomy death with dignity allowed her should be available to all terminally ill Americans.

Letter from Kay Milner, Sun City, Arizona — Self-Deliverance Was My Only Option

My Dear Friends,

By the time you receive this letter I will be gone. Please read this letter knowing I am doing what I want to do. Please don’t feel regrets for me. It is my choice.

I was informed on June 10, 1997, that I had lung cancer. I consulted a pulmonary specialist, a thoracic surgeon, and an oncologist. I had several chest x-rays, an extended breathing test, and a lung biopsy, followed by conferences of radiologists and all the other doctors. I was told that the cancer was of a fast growing type and even with major lung surgery and extensive, aggressive chemotherapy and radiation the chances of survival were only about 20% for a two year period, and even then I would be oxygen dependent for whatever time I had left to live. Faced with that grim prognosis, I immediately decided to have no surgery or treatment of any kind.

I have spent these last months getting my affairs in order and enjoying what few activities, events, and friends that I was able to enjoy. My thinking for years has been that death was not to be feared but should be as quick and painless as possible. Hospice care facilities and hospitals were not to my liking, mainly because of legal restrictions, and consequently I supported the idea of self deliverance and that is what I have done.

One-third of my estate will be donated to promote changes in legislation that will allow everyone to have more control over their last days alive. I hope that, in the future, you will give thought and support to any recognized right-to-die organization that gives each individual the option to die when and how they choose, without recrimination from the laws, insurance companies, religions, families, or any other outside influences.

You might not agree with what I have done and you might not ever want to consider self deliverance for yourself, but I hope you agree that I, and thousands of others in the same position as I was, should have the right of ending our lives as we wish to, without pain, debilitation, and suffering, and while we are still mentally and physically in control of our own destinies.

I have enjoyed your company and friendship immensely. It has been a great satisfaction to me and I consider it a privilege to have known you.

Good-bye, my friends.

Affectionately,

Kay

Why Do You Want to Keep Me Alive — and Tortured?

An Open Letter by Joe Stern

November 21, 1997

I have terminal cancer with no hope for cure or remission. At 87, I am still mobile, but in pain every moment I am awake. Drugs ease my pain, but do not, for a single minute, eliminate it. Soon I will require massive help. I dread the final few weeks with my family around waiting for me to die.

I would like to end my life when I require massive help to feed and dress myself. I don’t look forward to the increased pain and suffering. My government forbids me from a dignified assisted death.

If I were condemned to death, the government would bend over backward to make sure I didn’t suffer too long and that my death would as painless as possible. If I were being tortured in a foreign country, my country would protest loudly, but now it forces me to suffer a slow agonizing death.

Where does this barbarous prohibition come from? Is it due to some people’s religious beliefs? If that is the case, it is unconstitutional, as the Constitution tells us that Congress shall make no laws restricting freedom of religion. Others are forbidden from forcing me to adhere to their religious beliefs. Where else could such a prohibition come from? Can someone please tell me? Why do the people subject me to such torture? What gives them the right? Even animals are put to sleep humanely when they are in pain with no hope of recovery. Am I less than an animal?

When I say government, I obscure the blame. In our country, government derives its rights from the consent of the governed. It is people like some of you reading my words right now who instruct my government to continue torturing me.

But someone does benefit. Hospitals benefit. Drug companies benefit. Makers of hospital supplies benefit. They benefit at the expense of my family and all the people who could benefit from the money these corporations receive, in better health care, education or any number of other ways.

Think about this: Do you want to torture me? Do you want to help the health industry make profit from my suffering? Do you want to deny me the dignified assisted death I will soon desire? If so, why? Please give me one logical reason why my family should be emotionally and financially drained, and why my country’s resources should be given to this useless prolongation of life.

Why I Support Compassion & Choices in Arizona

Arizona End-of-Life Options is a broad coalition that evolved in part from an earlier Arizona chapter of Compassion and Choices. A number of years ago, leaders of that organization (some of whom are no longer with us) were asked why they got involved. Here are their answers.

From Jean Osborne: “Two Loving, Caring People”

I take this opportunity to relate two stories about why I got involved in the death with dignity movement. Stories about two wonderful, loving, caring people very close to me who died with anything but dignity. With their bodies full of cancer, they could not be completely anesthetized with any of the palliative care they received at the end of their lives.

My mother was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in December 1993 and died in April 1994. Hospice nurses came to our home to administer palliative care only in the last few weeks of her existence and, since they were unable to be there on a 24 hour a day schedule, there were many times when Mother would cry out in pain and there was nothing I could do for her. I was unable to administer drugs intravenously to relieve her suffering and she was unable to swallow the potent, liquid prescription. She slipped into a coma and had to be taken by ambulance back to the hospital. She died approximately five hours later.

The second agonizing death I witnessed was my significant other of 21 years. He was a retired Air Force General and fighter pilot, who had proudly served his country for thirty years. In 1989 he had to have his cancerous vocal chords removed. For almost nine years he lived a reasonably happy life and used the voice box apparatus designed for laryngectomy patients. In 1998 his cancer returned and ruthlessly spread throughout his body. In the end he was unable to communicate due to the fact that he could no longer hold the voice box to his throat and that device was his only contact with the world. Because of his special breathing needs, I was unable to care for him at home, and once again I was a helpless observer of an excruciating imminent death. This lugubrious event lasted for ten months and ended by withdrawal of all tubes connected to his fragile body.

As these two loved ones were perishing, I made a tacit promise to them that I would do everything in my power to change the way terminally ill humans are treated. I believe working with the Compassion & Choices organization is a good start.

From Karen Tyner: “The Tip of My Nose”

Call it a strong sense of my civil rights that brought me to join Compassion & Choices Arizona. I’ve always loved that phrase, “all laws stop at the tip of my nose,” and that includes my right to see to my own death if I choose to die with dignity.

From John Thaxton: “The Examined Life”

Like any good American, I grew up unaware of dying and death. These concepts were not part of public consciousness and were not even really allowable in “polite” conversation.

But experience, the best teacher in life, taught me that Death couldn’t be banished. A major injury years ago put me in great pain and made me realize that I would not want to continue living my life if that kind of pain were the price. Fortunately an operation put me back on the path of living well.

A few years later, my mother died, peacefully at home in no pain, cared for by her daughter, who was also a registered nurse. I learned to be grateful for my mother’s peaceful death and pondered my own. That led me to do volunteer work for a hospice, visiting dying patients.

My first and most memorable assignment was a man called L, a professional truck driver. Dying caught him on the freeway as he was driving his truck across the country and let him linger in a hospice in Denver until the end. He was miserable, angry, harsh, ungrateful, and in denial. He was also in pain and literally without a relative or friend in the world. Because he was indigent and friendless, his facility and care were substandard, far below what I would ever want for myself. The dollar speaks, even in dying. I sneaked him cigarettes, his one pleasure, for which he never thanked me. It was unpleasant visiting this lost soul, and he died a lonely and very sad death, with virtually no control over any aspect of leaving this world. Again, I learned about dying and death, but this time from the opposite side of the spectrum from my mother’s peaceful death.

The cumulative effect of these and other experiences illuminated and reinforced my hope to have a death I could look back on with satisfaction. Above all, I realized I wanted to die pain-free and with as much control as I could. I have always tried to live an “examined” life, seeking to make the best choices consciously and in harmony with my principles.

To have control over my dying process and death is just a continuation of how I have always lived. It is simply the last decision in the living process, and we all should have the right to create and direct the last act. Compassion & Choices supports this basic right and works to create the conditions that allow for dying with dignity. For this reason, I support CCAZ’s mission and work.

From Dean A. Myhr: “I Cried and Cried”

Like many of you, I have witnessed, first-hand, the “dying process” of so many people I have loved. And how degrading and embarrassing it must be for those who are in the final stages of that process — to not have the strength, the will nor the power to control anything, most importantly, “life itself.” As those I have loved were in that final process, I cried and cried, not only for losing them from my life, but most importantly the process that society has dictated to be appropriate and humane! How sad!!!!!

For the most part, we are a compassionate society! We are considerate and attentive to the wishes and needs of others. No individual, religious organization, nor government has the right to determine our individual desires when it involves making that final decision, an End-Of-Life-Choice. I applaud and support, whole heartedly, the goals of this organization.

From Paul Sachs: “Anything but Dignified”

My family has always believed in hastened death rather than prolonging a life without any acceptable quality. My brain dead father’s life was extended several times despite his medical power of attorney to the contrary.

My first wife died in pain from cancer. After cutting off nutrition she survived for over a week. She never left her bed in over a month. It was anything but dignified.

From V. J. Plummer: “Bow out Gracefully”

As a young dancer, I watched older dancers suffer because they hadn’t planned well. Their embarrassment was almost contagious. I promised myself that I would ‘bow out gracefully’. I specifically promised myself that I would leave show business when I began to appear to be 30 years old. Dancers, similar to athletes, are considered to be ‘over the hill’ once they are about 30 years old.

Little did I realize what a valuable lesson I was cultivating — one of the very few important lessons I was able to learn from others rather than having to experience the agony of the lesson myself. I learned to be able to apply the principle of “bowing out gracefully” to other activities in my life.

At the age of 32, I unexpectedly looked into a mirror and saw the 30-year-old-looking woman I had been waiting to see. I gave myself one year to find another occupation. One year later (to the day) I raised my hand and was sworn in to the Woman’s Army Corps. I changed costumes.

A few years before the 20-year anniversary of my military service, I analyzed the pro’s and con’s of continuing my military service beyond 20 years. As an older female in a male-dominated institution, I decided, again to “bow out gracefully”. I tired of over-compensating. Whether or not I could continue to prove that I was physically fit became less important than whether or not I wanted to continue to prove that I was physically fit. “Bowing out gracefully” was an easier decision than it had been as a dancer.

The ethical stance of the Compassion & Choices philosophy is compatible with my personal life stance. Quality of life is most important to me. I had no choice about how I entered life. I do have some choice in how I exit life. More than anything, though, I hope that I have the courage, foresight, and sense of timing to “bow out gracefully”.

From David Brandt-Erichsen: “As fundamental a human right as it gets”

As a fifth-generation direct descendant of famed abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Lucretia Mott, freedom-fighting is in my genes, so it is only natural that I have been an activist on medical aid in dying in Arizona since 1986, working toward this “last right.” Controlling my own destiny and the manner in which I die is as fundamental a human right as it gets. I am a life member of Compassion and Choices, and I hope my membership does not expire for a very long time. But when it’s my time to go, I want it to be on my terms, not somebody else’s!